California State University, Northridge will help the CSU digitize 10,000 documents and 100 oral histories related to the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

The CSU Japanese-American Digitization Project is a collaboration between 15 CSU campuses to create a public, online repository of internment-related documents, audio files, photographs and oral histories, as well as materials documenting the era’s Japanese-American life in California. The project is spearheaded by CSU Dominguez Hills’ archives and special collections, which was awarded a $321,554 grant from the National Parks Service to complete the digital archive over two years.

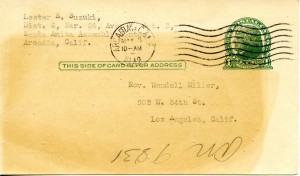

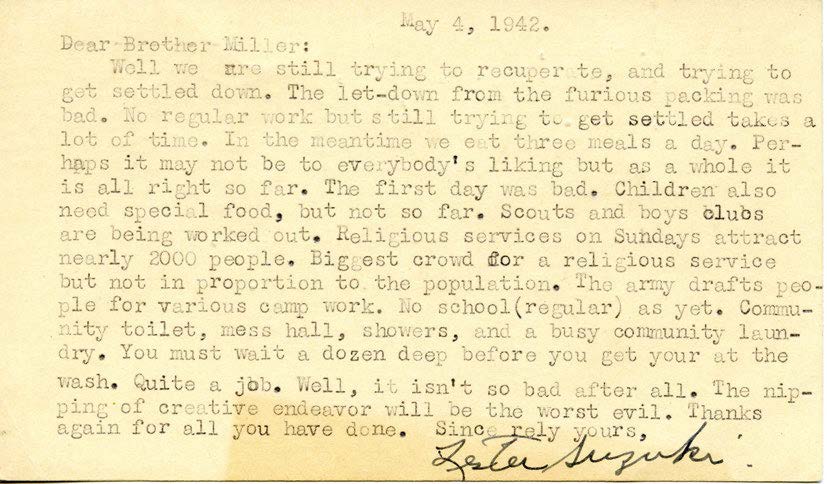

CSUN’s Head of Special Collections and Archives Ellen Jarosz said each campus library’s special collections has different materials that are complementary. CSUN’s collection in the Delmar T. Ooviatt Library mostly is composed of oral histories; newsletters from various camps produced by internees; correspondence, such as letters passed back and forth between family members in camps and those not in the camps; and clipped newspaper and magazine articles.

“The website will be really valuable,” Jarosz said. “The materials themselves slowly deteriorate; over time, they break down. It’s important to capture them before they crumble apart.”

Roughly 120,000 Japanese-Americans, most of whom were United States citizens, were

forcibly relocated to camps, where they lived in squalid conditions for three years — most of them losing their homes and livelihoods. The majority of internees were from the West Coast, many of them from California.

CSUN Asian-American studies professor Edith Chen lauded the CSU for the project.

“Anything the university can do to say we value the history and perspectives of Asian-Americans sends a message out there about what is important to learn and preserve,” Chen said.

Japanese-Americans are one of the nation’s smallest ethnicities, and their population is not growing, said Chen. She compared the former internees, whose numbers are dwindling as they age, to libraries that are burning down — losing valuable information as the population dwindles.

CSUN’s Asian-American studies department has tried in the past to do a similar kind of digitization project, but technology was not as accessible and there was a lack of funding, she said.

Asian-American studies lecturer Laura Uba, whose parents were interned during WWII at the camp in Heart Mountain, Wyo., said the portal could be “fantastic” for students and members of the public interested in Asian-American history. She said it could highlight a part of history that often receives little attention and is misrepresented.

“This archive can dispel the sophomoric narratives that still dominate so much of the middle and high school curriculum, and instead provide more realistic, illuminating and useful perspectives,” Uba said. “Away from the West Coast, many Americans know little more than that the camps existed. Those who do are often misinformed because they rely on what family elders have said, but the latter formed their opinions based on the contemporaneous rantings [that] racist newspapers spread — and sugarcoated narratives the government fed the American public. So, they still haven’t learned about what the Japanese-Americans really experienced, much less why the government really acted as it did.”

Uba said the oral histories could be important. Depending on what the survivors chose to expose and if they were particularly introspective, the oral histories could “go a long way toward filling a hole in the corpus of scholarly knowledge — precisely because they are testimonies.”

“Presenting some people with concepts and facts moves them to appreciate the importance of the internment experience for the United States, as well as for Japanese-Americans specifically,” Uba said. “But many people need to feel a connection to the people studied. These testimonies can be just the link needed to stir empathy and thereby arouse interest in the internment experience and see its importance.”