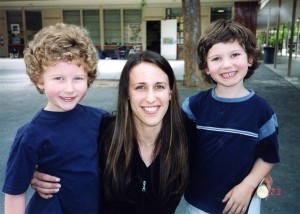

Twins Tyler (left) and Hunter Gordon (right) with their kindergarten teacher Kimberly Jones. Photo courtesy of Lynn Gordon.

Separating twins in kindergarten — a common practice in schools across the country — can be traumatic for children and is often against the wishes of both the children and their parents, according to a new study by California State University, Northridge education professor Lynn Melby Gordon.

Gordon’s study, “Twins and Kindergarten Separation: Divergent Beliefs of Principals, Teachers, Parents, and Twins,” was published last week in the journal Educational Policy and is the first to explore the separation of twins in kindergarten by directly comparing and examining the beliefs of elementary school principals, kindergarten teachers, parents and twins.

“To put it simply, my research does not support the mandatory school-separation policies for all twins that are so prevalent in school districts across the country,” said Gordon, a professor in CSUN’s Department of Elementary Education and parent of twins herself. “School leaders should know that when a pair of twins has a genuine preference to stay together in school, it does not necessarily indicate a pathological co-dependence, a lack of individuality or an inability to make friends with other children. It is, more likely, simply indicative of a healthy, supportive relationship.”

As part of her research, Gordon surveyed principals, kindergarten teachers and preschool- and kindergarten-age twins and their parents about separating twins when they begin their formal educational experience in kindergarten.

She found that principals are much more likely to believe that twins should be separated in kindergarten than the young twins themselves, their parents and even kindergarten teachers. While a majority, 71 percent, of the principals she surveyed said they felt twins should be separated in kindergarten, only 49 percent of the teachers, 38 percent of the parents and 19 percent of the preschool and kindergarten twins agreed.

“A troubling finding from the group of principals surveyed is that over half of separation-favoring principals believe that twins do better academically when they are placed in separate classes, and almost one quarter erroneously believe that twins do better academically when they are placed in separate classes,” Gordon said. “The presumptions are not supported by the existing body of twin research. Instead, studies tend to show either no difference in the academic achievement of twins placed together versus apart or that academic achievement tends to be better when the twins are placed together.”

She found that 81 percent of preschool and kindergarten twins want to stay together in kindergarten, but about 58 percent of twins are separated into different classes. Female identical twins are most likely to report wanting to stay together in the same class in kindergarten.

Gordon said that most parents favor joint placement of twins in kindergarten.

“Perhaps not surprisingly, 95 percent of parents believe they know their kids best, and believe that schools should try to honor their class placement requests for twins,” she said.

She noted that kindergarten teachers would not mind having a set of twins in their class.

Three percent of all twins who are placed in separate classes are very traumatized by kindergarten separation, and an additional 17 percent are somewhat traumatized, according to parents. In the meantime, 69 percent of principals believe that separation is probably a little traumatic, and six percent believe that separating twins is very traumatic.

Gordon said there are instances when twins are likely to benefit from class separation.

“For example, when twins display pronounced behavior problems with one another at home or in preschool, parents recognize this to be a clear and practical reason to separate those individuals at least for a few hours a day while they are in school,” she said. “But the study’s primary conclusion is that, unless there is a compelling reason to separate twins, it is often best to keep them together, at least in kindergarten.”